Q Magazine September 2017

September 2017 | |

| Categories | Music |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Monthly |

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

James Lavelle featured across six pages in the September 2017 issue of Q Magazine.

Transcript

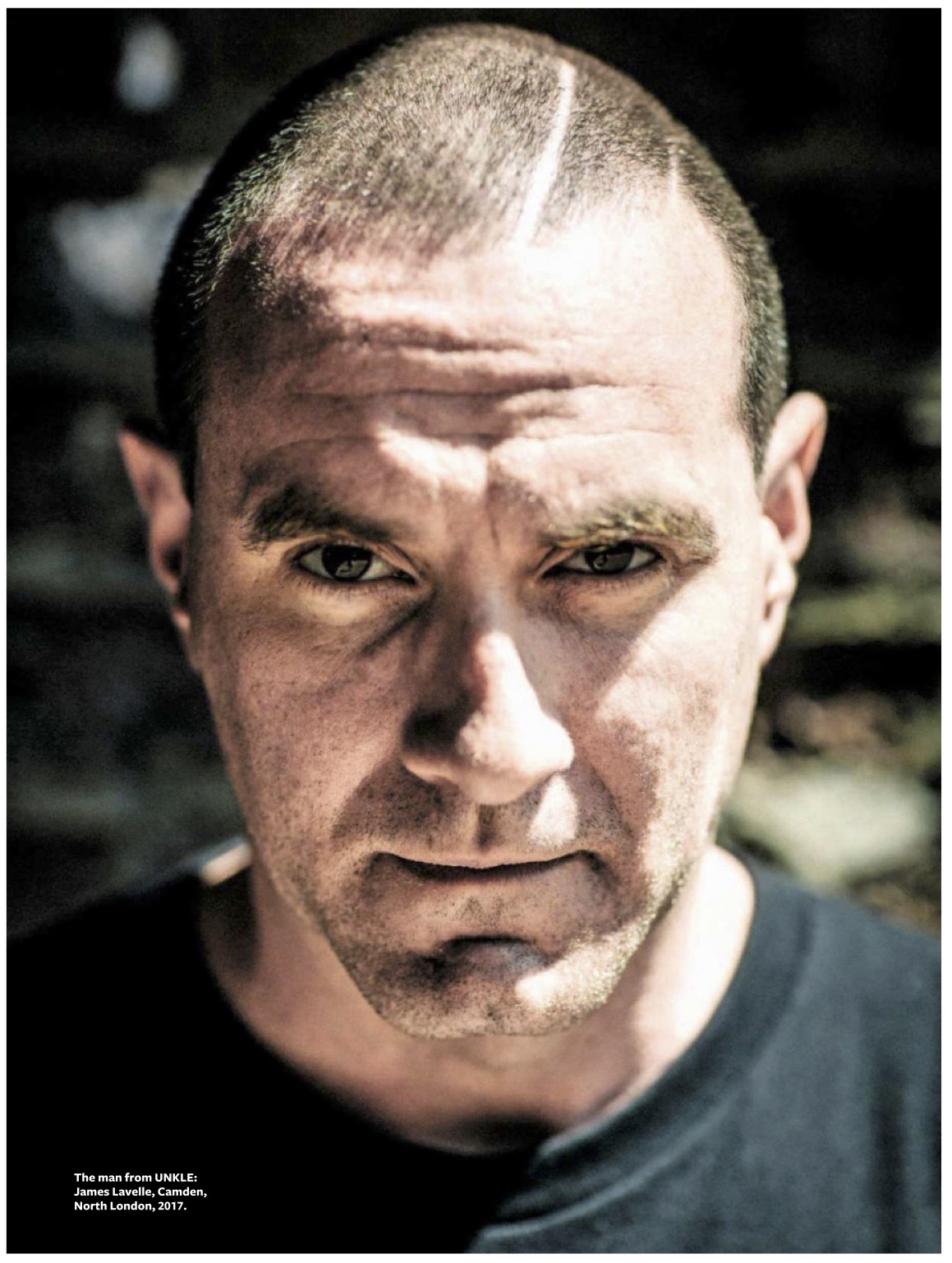

Maverick: James Lavelle

This month’s cult hero is the man behind UNKLE, founder of the Mo’ Wax label, and the inventor of trip-hop.

James Lavelle was the boy wonder who, as the founder of the Mo’ Wax label, launched DJ Shadow and invented trip-hop. But it was as the director of his great collaborative project UNKLE that he proved himself to be a visionary lightning rod, bringing Thom Yorke, Mike D and Richard Ashcroft together. By 2003, though, he was nearly bankrupt. And then the trouble really started. Dorian Lynskey hears his story. n February 1998, James Lavelle celebrated his 24th birthday with a party at London’s Met Bar in the company of Noel Gallagher, Richard Ashcroft, Ian Brown, Carl Craig, Alexander McQueen and an Everest of cocaine. It was, he says happily, “a fucking amazing night”. At that moment Lavelle was the boy wonder of British music. He was the hipster geek whose Mo’ Wax label, home to DJ Shadow and his own UNKLE project, was the impeccably cool junction box for an international network of musicians, DJs and designers. When he was negotiating a deal with A&M in 1995, his gutsy deal-breaker was a painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat. By 2003, however, his star had plunged. Mo’ Wax was dead and Lavelle was in debt to the tune of £ 270,000. He had to sell the Basquiat. “It was beautiful,” he says wistfully, “while I had it.” It’s been a long, intense journey, hence the title of the powerful new UNKLE album, The Road: Part 1. Raiding the archives for Mo’ Wax’s 21st anniversary in 2013, curating the Meltdown festival in 2014, and participating in a new documentary, Artist & Repertoire, have all conspired to make Lavelle reassess his past and ask himself why he makes music. “The last 13 years have been fucking tough financially,” he says over cartons of Korean food in his manager’s office in Camden. “In one way I’m probably insane to keep doing what I do. Anybody rational would have stopped trying to do UNKLE years ago.” He laughs oddly. “I’ve put myself through quite extreme situations, both financially and emotionally. But then I got used to that very young.” The Road: Part 1 opens with actor Brian Cox saying: “Have you looked at yourself ? And have you thought about the mistakes you’ve made, and the road you’ve walked?” James Lavelle has.

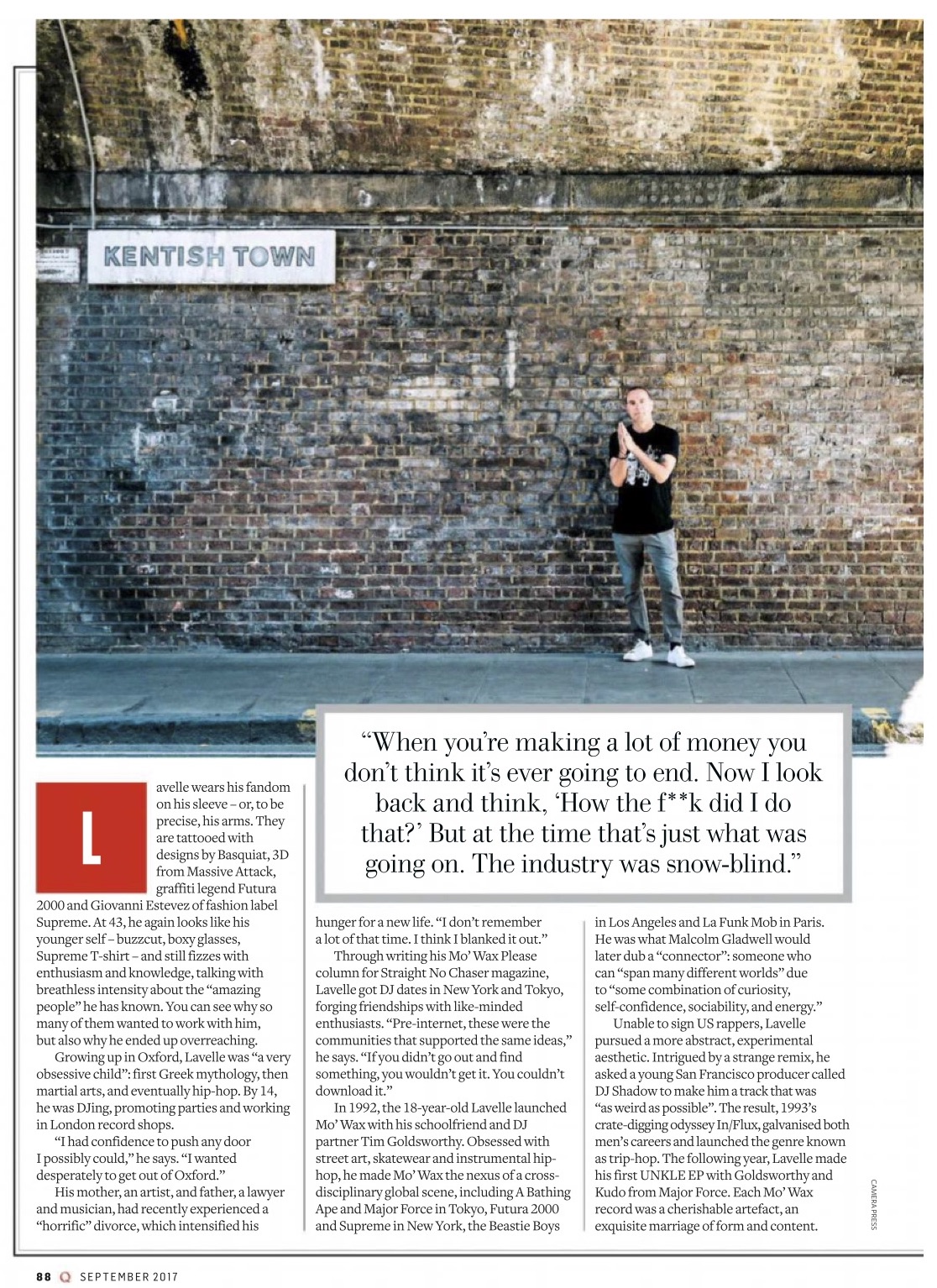

Lavelle wears his fandom on his sleeve – or, to be precise, his arms. They are tattooed with designs by Basquiat, 3D from Massive Attack, graffiti legend Futura 2000 and Giovanni Estevez of fashion label Supreme. At 43, he again looks like his younger self – buzzcut, boxy glasses, Supreme T-shirt – and still fizzes with enthusiasm and knowledge, talking with breathless intensity about the “amazing people” he has known. You can see why so many of them wanted to work with him, but also why he ended up overreaching. Growing up in Oxford, Lavelle was “a very obsessive child”: first Greek mythology, then martial arts, and eventually hip-hop. By 14, he was DJing, promoting parties and working in London record shops. “I had confidence to push any door I possibly could,” he says. “I wanted desperately to get out of Oxford.” His mother, an artist, and father, a lawyer and musician, had recently experienced a “horrific” divorce, which intensified his hunger for a new life. “I don’t remember a lot of that time. I think I blanked it out.” Through writing his Mo’ Wax Please column for Straight No Chaser magazine, Lavelle got DJ dates in New York and Tokyo, forging friendships with like-minded enthusiasts. “Pre-internet, these were the communities that supported the same ideas,” he says. “If you didn’t go out and find something, you wouldn’t get it. You couldn’t download it.” In 1992, the 18- year-old Lavelle launched Mo’ Wax with his schoolfriend and DJ partner Tim Goldsworthy. Obsessed with street art, skatewear and instrumental hiphop, he made Mo’ Wax the nexus of a crossdisciplinary global scene, including A Bathing Ape and Major Force in Tokyo, Futura 2000 and Supreme in New York, the Beastie Boys in Los Angeles and La Funk Mob in Paris. He was what Malcolm Gladwell would later dub a “connector”: someone who can “span many different worlds” due to “some combination of curiosity, self-confidence, sociability, and energy.” Unable to sign US rappers, Lavelle pursued a more abstract, experimental aesthetic. Intrigued by a strange remix, he asked a young San Francisco producer called DJ Shadow to make him a track that was “as weird as possible”. The result, 1993’ s crate-digging odyssey In/Flux, galvanised both men’s careers and launched the genre known as trip-hop. The following year, Lavelle made his first UNKLE EP with Goldsworthy and Kudo from Major Force. Each Mo’ Wax record was a cherishable artefact, an exquisite marriage of form and content.

“I wasn’t being intellectual about it,” Lavelle says. “I just wanted to do as much as I possibly could and creatively outdo everyone else in every possible way.” What kind of boss was he? “Oh, a nightmare. Erratic. Difficult. I think the volume of work I put on people was exhausting. But I’ve never bullied or ripped anyone off. I was never someone like that.” Though less mythologised than Britpop, Mo’ Wax was much more emblematic of the 1990s’ energetic eclecticism and just as representative of its snowballing excess. Lavelle couldn’t help himself. The 1994 compilation Headz contained 18 tracks; two years later, the vinyl version of Headz 2 bulged with 70. With the music industry at its pre-Napster peak, A&R wars became absurd. Lavelle re-enacts his attempt to sign the drum’n’bass producer Photek. “You’re on the phone, Virgin’s on the phone, BMG’s on the phone. It was like a fucking auction. The next minut minute it’s like, ‘Deal’s done, they’ve just given him a Maserati.’ And you’re like, ‘Fuck, why didn’t we give him a Maserati?’” He mimes snorting an anaconda of cocaine. “It was insane.” His lifestyle was also insane. He spent everything he had on art, clothes, travel, Star Wars memorabilia (most of it since sold) and ambitious projects. He began taking coke to get by in a “laddish” industry, to mingle with the new glitterati of pop, art and fashion, and to keep up with the physical demands of his job. He says without pride that he partly inspired one of the characters in John Niven’s bacchanalian satire Kill Your Friends. In 1997, amidst all this mayhem, he became a father. “It was all too much, too soon, and with no understanding of what I had and how to deal with it,” he says. “When you’re making a lot of money you don’t think it will ever end. Now I look back and think, ‘How the fuck did I do that?’ At the time that’s just what was going on. The industry was snow-blind.” Lavelle staked his reputation on UNKLE’s 1998 debut album Psyence Fiction, a gruellingly ambitious transatlantic collaboration with DJ Shadow. This big, brooding, sci-fi-themed album featured Thom Yorke, Richard Ashcroft, Mike D and members of Talk Talk and Metallica, and spawned merchandise and action figures. Lavelle even approached Stanley Kubrick to direct one of the videos. Anything was possible. And then it flopped. “It started with a fanfare of joy and became the beginning of the end,” he says heavily. “It’s not perfect but it’s a pretty amazing record for the context. I don’t know how we did it. The way people perceived my involvement in that record was very upsetting. I wasn’t the golden boy any more.” To the critics, Psyence Fiction was the trip-hop Be Here Now. One called it “a grandiose, bloated, egotistical folly,” pinning the blame squarely on Lavelle. Not being a musician, songwriter or programmer, Lavelle struggled to articulate his role. “I’m like a film director,” he says now. “My greatest heroes are people like Stanley Kubrick – you create a world and everything that goes in it.” He seizes another analogy: “I’m a collagist. The great art of DJing is putting things together that aren’t always meant to work.” His detractors claimed he was a slick networker with no musical talent and that UNKLE was his vanity project but the accusation that Lavelle was a businessman pretending to be an artist was, in fact, upside down. “I didn’t know about business!” he says. “I’d been portrayed as being the next Richard Branson but in my youthful, anarchic way I was like, ‘Fuck that!’ You don’t see very far when you’re that age. You’ve got to do it all now.” Mo’ Wax moved to Island and then to XL, still releasing fine records (hip-hop duo Blackalicious, veteran composer David Axelrod), but no longer in the vanguard. Headz 3, the compilation to end them all, was never finished. “Again my wonderful way of making something so exorbitantly massive that it never happened,” Lavelle says drily. He notes that his A&R protégé Nick Huggett stayed with XL and proceeded to discover M.I.A., Dizzee Rascal and Adele. “If Mo’ Wax was still around, would I have let Nick sign Adele?” he muses. “Would it have been appropriate? Probably not.” In 2002, Lavelle quietly let the label die. “Because of my relationship with my father and the divorce, I had a mechanism of moving on and shutting things down,” he reflects. “I don’t really remember what happened at the end but I basically just walked away. I’d had enough. I turned my back on everything.”

During the dog days of Mo’ Wax, Lavelle heard that Damon Albarn was working on a hip-hopinspired collaborative project called Gorillaz. Over the phone, Albarn jokingly told him, “Yeah, I’m doing the ultimate UNKLE rip-off album!” During the ’ 00s, Lavelle felt like yesterday’s man. Gorillaz was the bigger, brighter version of Psyence Fiction, right down to the action figures. XL’s Richard Russell was the reigning hipster mogul, with much sharper business instincts. Pharrell became A Bathing Ape’s new musical ambassador. DFA Records replaced Mo’ Wax as the clued-up independent label that could do no wrong. One of DFA’s founders was Tim Goldsworthy, who compounded the symbolism by dating Lavelle’s ex-girlfriend. “The press pitted me against them and now Tim was the genius of UNKLE,” Lavelle frowns. “Are you fucking kidding me? It was just awful. I think that threw me into my worst period of excess because I was hiding from what was going on emotionally.” Suddenly he stands up to leave the room. “Do you mind if I have a cigarette and get my brain back into gear? It’s a lot of stuff I’ve closed off in my head.” One fag later, he resumes the story. Needing both money and distraction, Lavelle buried himself in DJing, holding down simultaneous residencies in London, Berlin, Tokyo, Singapore and LA. It filled the void left by Mo’ Wax but he became as obsessive about hedonism as he had been about hip-hop or kung fu. “It was an excessive, nocturnal time that became more and more detrimental.” At the same time, Lavelle was falling in love with rock. He befriended Josh Homme, Mark Lanegan and producer Chris Goss, all of whom worked on subsequent UNKLE LPs, starting with 2003’ s Never, Never, Land. His timing, he notes, was financially unfortunate. He scaled back DJing to start a live band in 2007, on the cusp of the EDM explosion. Most bands only break up once, maybe twice, but UNKLE’s unusually fluid identity means that Lavelle is always parting ways with his studio partners: Goldsworthy, Shadow, Richard File, Pablo Clements. “It sounds silly but every one of the key people I’ve worked with in my life I’ve loved,” he says. “Maybe it’s too intense sometimes. Every record is like a love affair and a break-up.” His hedonism and strained friendship with Clements both came to a head while making and touring 2010’ s Where Did The Night Fall, the last UNKLE album for seven years. In a grim coda to the story, regular vocalist Gavin Clark committed suicide in 2015. “I’d been worried about him for a long time but our relationship had reached an impasse,” Lavelle says hesitantly. “It’s hard to talk about. UNKLE isn’t a band where somebody should kill themselves. It ended up so bloody rock’n’roll and that wasn’t really what it should be. I asked myself: ‘What the hell is this about? Why do you make records? This pain, this drama, has just got too much.’” At 37, Lavelle finally slowed down, licked his wounds and rebuilt his confidence with projects such as Meltdown and the audacious cross-disciplinary extravaganza Daydreaming With Stanley Kubrick, on which he “worked for five years and didn’t make one penny”. Eventually, schoolfriend Matthew Puffett and young singer-songwriter Jack Leonard became his new partners in UNKLE. When Lavelle revived the project, he had two priorities. One was to foster stability and minimise stress. “It’s been a 99.9 per cent joyous experience,” he says. “I always felt that I was building a pyramid from the top down. This time we started from the bottom.” The other was to prove that UNKLE was never an A&R-led Frankenstein’s monster but a deeply personal statement. “Every record is a diary of a period in my life. It’s always hard when people look at me as a conceptualist and architect. It’s not that intellectual. It’s more from here.” He thumps the left side of his chest. “It’s about love and regret and all of that stuff.” Just as importantly, he feels that Mo’ Wax’s legacy is finally getting its due. Norman Cook once compared Lavelle to Grandmaster Flash, the pioneer who fell by the wayside, and himself to Dr Dre, the latecomer who made all the money. “Your problem,” he told Lavelle, “is that you’re into the creation of things but you’re not good at being patient and following through.” It’s true. Lavelle was an early champion of many things that are now mainstream, including all-star collaborations, street art, audiovisual DJ shows and partnerships between musicians and fashion labels. “What we created as a universe is pretty much the staple diet of the creative industry now,” he says. “But I didn’t benefit from the success because I was constantly moving on. For a long time I wasn’t seen as being part of that movement and that was frustrating. People can understand it now. Most of what I was involved with is now bootlegged in Camden.” Lavelle needs another cigarette but before he goes he recommends a scene in Artist & Repertoire: a clip from an MTV interview he gave when he was 21. “I sit there and say, ‘I don’t really care about the money. At the end of the day, if it all goes wrong, I’ve got a load of beautifully designed records that people will collect forever.’” He shrugs, amused rather than bitter. “It’s ironic.”

Scans

-

Cover

-

Page 86

-

Page 87

-

Page 88

-

Page 89

-

Page 90

-

Page 91